There’s a movement afoot in the home performance industry, and it’s being driven by a combination of technology, business, and culture. Finally, after years of working on all the separate pieces of the industry — research and development, training, installation, quality control — we can integrate these separate endeavors. For a lot of us in the home performance industry, it’s about time. We now have a suite of tools that offer the possibility of pushing the implementation of high performance construction into the mainstream.

This industry-shifting evolution is being driven in various ways by evolving sensors, smarter software, connected devices, and streaming data. None of these technologies are new at this stage, since we’ve had versions of each in use for several years. But we’re now seeing a rapid shift in how these tools are used because they’ve all become more robust, more widely available, and more connected.

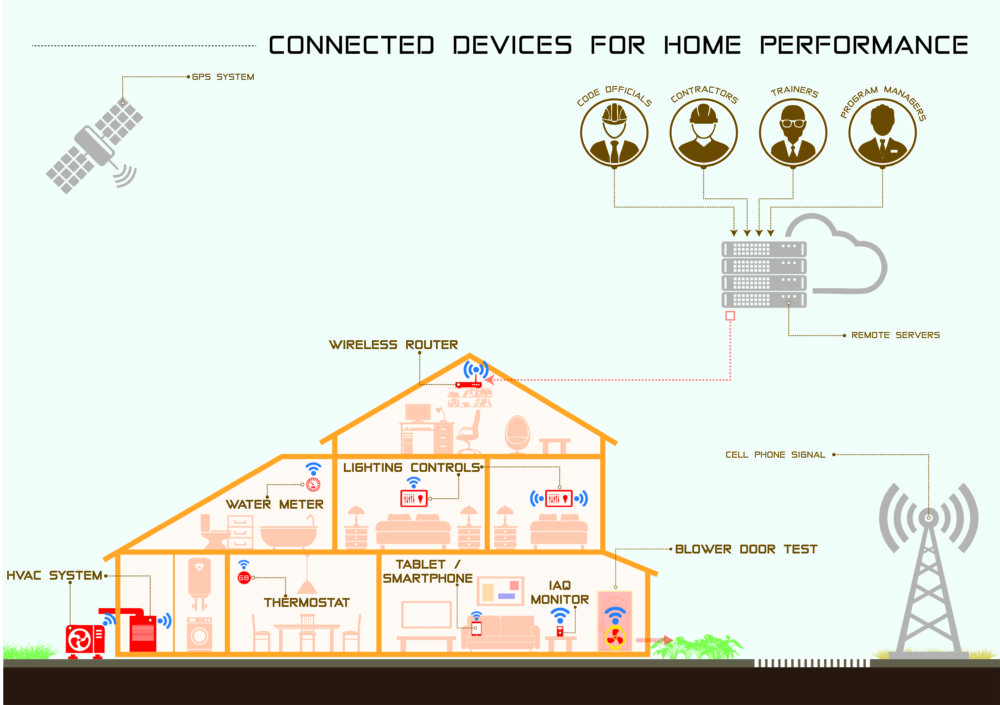

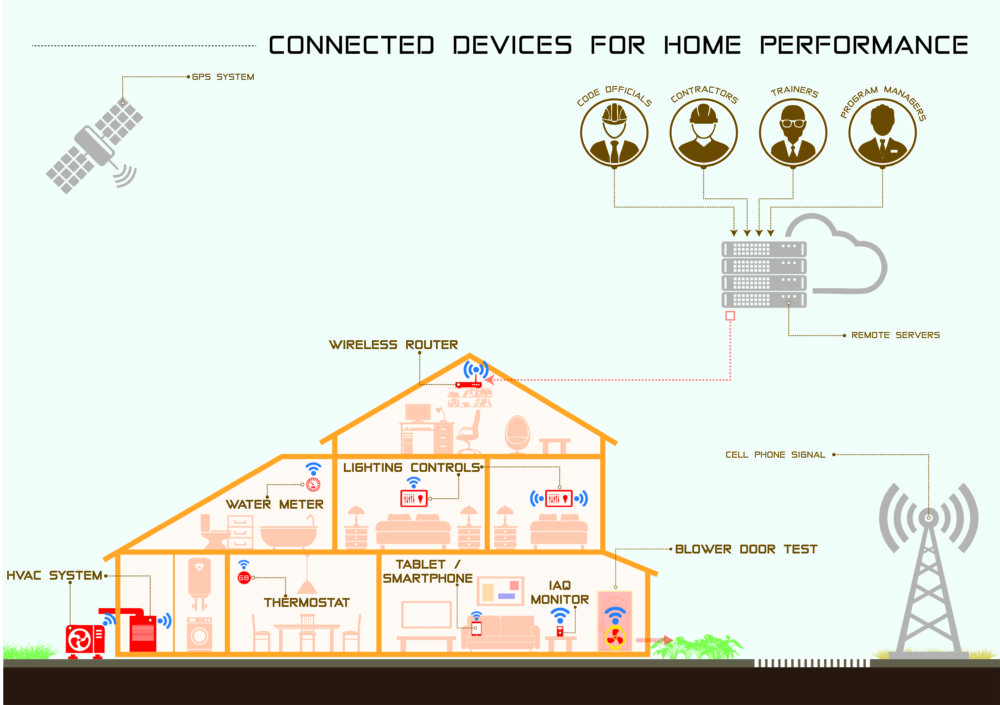

There is a lot of signal in the air in the modern house, connecting devices both local and remote. We’re seeing increasing connectivity among them as developers agree on communications protocols. Opportunities will arise over the next few years as housing professionals, trades-people, and homeowners figure out how to take advantage of these new data streams.

Transparent Data and Clear Market Signals

This increased connectivity between devices is undeniably the most impactful of these changes. It also fosters greater industry coordination, as the work done by manufacturers in the lab, trainers in the classroom, technicians in the field, and quality control staff in the office can now be connected, compared, and aligned in an integral process. The possibility of creating real synergy among all these disparate parties, who often struggle to work together because of mixed incentives and obscured market signals, will create a huge shift in how the home performance industry operates. More data is becoming more available, it’s more transparent, and this is good for everyone involved.

We’re not there yet, though, and the ideal of one big harmonious industry that’s informed by facts, not fiction, may still be off in the future. But it’s clear that this current round of rapid evolution, driven by data on the actual performance of our homes, will support the promulgation of measures that are proven to improve our homes. It’s getting more and more difficult to kid ourselves about what works and what does not work when it comes to high performance construction. Transparent data and clear market signals are increasingly available to support the design, funding, and installation of high performance construction measures.

The Impact of Connected Devices

When it comes to dispersal of information, things tend to happen quickly. Consider how your learning channels have shifted over your lifetime: remember encyclopedias, road maps, and phone books? In all industries, the smart money is flowing towards remote communication, honest evaluation, and targeted management. In the construction and home performance industries, this is changing how we evaluate, tune, and maintain equipment in the home. By integrating data seamlessly into day-to-day tasks, these devices will not only make life easier for home performance practitioners and program managers, but could effectively help bridge some of the longstanding cultural and practical differences between the home performance industry and mainstream construction.

Safety, efficiency, and comfort. All equipment operates best when installed, commissioned, and maintained according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Connected devices that can be configured to provide intuitive real-time information make it easier than ever to set up equipment so it’s responsive to conditions in the home. The best example here is Foobot, a super-friendly consumer-level indoor air quality monitor that can provide smart control of HVAC systems. When equipment can respond to actual events—rather than relying on a settings established at installation—we’re much more apt to reach the holy grails of safety, efficiency, and comfort. And with data streams that are both immediate (“Your furnace filter is ready for replacement”) and long-term (Your average particulate count is highest on weekends in winter”), consumers are increasingly willing to pay for this type of actionable guidance.

Safety, efficiency, and comfort. All equipment operates best when installed, commissioned, and maintained according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Connected devices that can be configured to provide intuitive real-time information make it easier than ever to set up equipment so it’s responsive to conditions in the home. The best example here is Foobot, a super-friendly consumer-level indoor air quality monitor that can provide smart control of HVAC systems. When equipment can respond to actual events—rather than relying on a settings established at installation—we’re much more apt to reach the holy grails of safety, efficiency, and comfort. And with data streams that are both immediate (“Your furnace filter is ready for replacement”) and long-term (Your average particulate count is highest on weekends in winter”), consumers are increasingly willing to pay for this type of actionable guidance.- Supervision and training. Field staff can’t do their job without metrics for performance. The best technical training is delivered in response to an immediate need. Connected devices show technicians what needs to be done, and I suspect that in the near future we’ll see a lot of on-the-job training delivered via these just-in-time systems that peer into the technician’s work (“Hey Jim, it looks like you may want to check the charge on the refrigerant. Here’s a video that shows the procedure.”). It may sound intrusive to have your supervisor looking over your shoulder like this, but in fact the field technician on a construction site is one of the few people in the modern workplace who often work alone and without supervision. These connected devices will improve the quality of everyone’s work by aligning training with the proven needs of staff members.

Quality control. You can’t manage that which you don’t measure. Connected devices provide insight into the operation of systems that have often been ignored for lack of reliable ongoing data. Take a look at the Retrotec rCloud system, for example, to see how quality control can be fully integrated into the construction process. This process of remote quality assurance has also been recognized by RESNET, with a movement underfoot in that organization to allow virtual site visits by their Quality Assurance Designees (QADs) that utilize technologies such as rCloud, photo-equipped drones, and the new EPA app RaterPro. It’s a hopeful future: we’ll achieve true quality control when it becomes an integrated part of the jobsite, rather than an occasional visit by a visiting auditor with a clipboard.

Quality control. You can’t manage that which you don’t measure. Connected devices provide insight into the operation of systems that have often been ignored for lack of reliable ongoing data. Take a look at the Retrotec rCloud system, for example, to see how quality control can be fully integrated into the construction process. This process of remote quality assurance has also been recognized by RESNET, with a movement underfoot in that organization to allow virtual site visits by their Quality Assurance Designees (QADs) that utilize technologies such as rCloud, photo-equipped drones, and the new EPA app RaterPro. It’s a hopeful future: we’ll achieve true quality control when it becomes an integrated part of the jobsite, rather than an occasional visit by a visiting auditor with a clipboard.

Example: Connected Comfort Systems

Take the simple forced air heating and cooling system that’s installed in millions of North American homes. It should be simple enough to install so it operates properly, but research has shown time and time again that several issues—especially the twin pressure points of poor airflow and incorrect charge—keep these systems from operating at anything close to their peak efficiency.

But when you add on-board sensors and diagnostics (whether installed by the manufacturer or as aftermarket items), connecting the data stream to a local network, and giving everyone involved access to the data, suddenly issues like airflow and charge become simply check-listed items that determine who gets paid and when. This simple feedback loop rewards good installers, reduces finger-pointing among all parties, and takes us a long ways toward embedding energy efficiency, comfort, and safety into mainstream construction.

Connected thermostats, such as Ecobee, LuxGEO, and Nest clearly have a place in these connected comfort systems, especially when they connect with equipment from other manufacturers. Honeywell, for example, recently launched an API (application programming interface) for their home thermostats that allows third parties to write custom applications that integrate their equipment with Honeywell equipment. These connected devices are also being pressed into increasing roles in demand response systems, such as the one offered by utility partner Opower, that allow utilities to shape their loads and reduce peak loads by managing equipment remotely. I suspect that manufacturers who don’t take this open approach will face shrinking markets.

Example: Connected Diagnostic Systems

Some connected devices produce instantaneous readings that are utilized during the process of construction, commissioning, or retrofit jobs. The rCloud system, for example, captures data from blower door and duct tests, connects to existing networks, and streams the geo-tagged and time-stamped data to secure servers. From there, users can share selected access to the data with other parties. It’s an obvious connection between field personnel and staff who manage their work.

By sharing data with quality assurance (QA) people, a new level of job-site supervision is possible, with less opportunity to falsify data or ignore improperly trained personnel. Having access to test data closes the loop on training, too: when suspect data is reviewed in real time by remote colleagues, it creates a good opportunity for on-the-job training. When the QA people see a problem, they can offer advice, and the technician can update their procedure.

Example: Connected IAQ Monitors

Connected devices are not just about comfort systems or envelope integrity, either. There’s a whole new batch of reasonably-priced consumer-level devices on the market (including Awair, Foobot, NetAtMo, and others) that measure and report various attributes of indoor air quality (IAQ). Some provide only instantaneous information to the homeowner, which will build awareness for the user, but doesn’t offer the ability to compare IAQ over time. The best home monitors include data-logging that shows trends, and connectivity that allows remote monitoring and management. A few, like the Foobot, are available with an interface that controls ventilation equipment—a good approach for those pollutants such as moisture or particulates that can be effectively managed with dilution or filtration.

A “Gateway” Device for Homeowners? There is plenty of debate within industry about the correct metrics and responses for managing IAQ, but it’s clear that the internet of things is about to shift how homeowners interact with their buildings AND with their service people. Most homeowners have little awareness of the nuances of their home’s operation, and having easy access to real-time data about their home may jump-start their interest in managing their home’s performance in general. One need look no further than the success of smartphone apps like CreditKarma and Mint, which function respectively as “gateways” for credit score and personal finance data, for examples of how convenience, transparency, and connectedness can transform consumers’ relationship with information. The devices we have available right now may not be perfect, but the fact that homeowners can now see what’s happening in their homes is a good start.

A “Gateway” Device for Homeowners? There is plenty of debate within industry about the correct metrics and responses for managing IAQ, but it’s clear that the internet of things is about to shift how homeowners interact with their buildings AND with their service people. Most homeowners have little awareness of the nuances of their home’s operation, and having easy access to real-time data about their home may jump-start their interest in managing their home’s performance in general. One need look no further than the success of smartphone apps like CreditKarma and Mint, which function respectively as “gateways” for credit score and personal finance data, for examples of how convenience, transparency, and connectedness can transform consumers’ relationship with information. The devices we have available right now may not be perfect, but the fact that homeowners can now see what’s happening in their homes is a good start.

Bottom Line: Why This Matters to Housing Professionals

Connected devices, and the sharing of accurate information that they allow, are driving this next evolution in housing. There will surely be winners and losers in this shifting marketplace, but I think that the performance of our buildings can only improve, and this will be good for everyone. You’ll be wise to consider where you will fit into this changing marketplace, for there will be both opportunity for smart forward-looking organizations AND a few dead-end industry sectors that suffer the fate of encyclopedias, road maps, and phone books.

— Chris Dorsi. (contact)

Portions of this article were first published in Home Energy Magazine.

A “Gateway” Device for Homeowners? There is plenty of debate within industry about the correct metrics and responses for managing IAQ, but it’s clear that the internet of things is about to shift how homeowners interact with their buildings AND with their service people. Most homeowners have little awareness of the nuances of their home’s operation, and having easy access to real-time data about their home may jump-start their interest in managing their home’s performance in general. One need look no further than the success of smartphone apps like CreditKarma and Mint, which function respectively as “gateways” for credit score and personal finance data, for examples of how convenience, transparency, and connectedness can transform consumers’ relationship with information. The devices we have available right now may not be perfect, but the fact that homeowners can now see what’s happening in their homes is a good start.

A “Gateway” Device for Homeowners? There is plenty of debate within industry about the correct metrics and responses for managing IAQ, but it’s clear that the internet of things is about to shift how homeowners interact with their buildings AND with their service people. Most homeowners have little awareness of the nuances of their home’s operation, and having easy access to real-time data about their home may jump-start their interest in managing their home’s performance in general. One need look no further than the success of smartphone apps like CreditKarma and Mint, which function respectively as “gateways” for credit score and personal finance data, for examples of how convenience, transparency, and connectedness can transform consumers’ relationship with information. The devices we have available right now may not be perfect, but the fact that homeowners can now see what’s happening in their homes is a good start.