We live in the most extraordinary of times, with unprecedented access to ideas, stuff, and people. This new flood of resources, as I see it, springs from a convergence of several factors: new communication tools, widespread wealth, and a mixing of social strata, among others. And though we could discuss this opening on several levels, this article addresses the sharing of information on the business and technology of high performance construction as it’s being developed on both sides of the Atlantic.

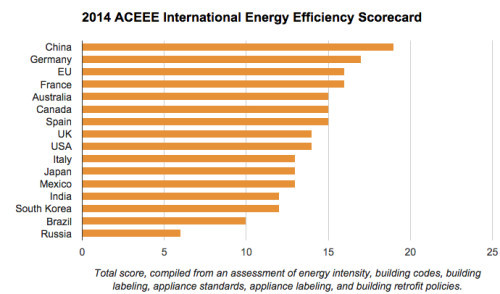

The 2014 International Energy Efficiency Scorecard, produced by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), rates the overall efficiency practices of 16 of the world’s largest economies in each of four categories: National Efforts, Industry, Transportation, and Buildings. When it comes to buildings, North Americans could learn a few things from their international counterparts. Look at the chart: out of a possible total score of 25 for buildings, the U.S. receives a score of only 13, with Canada scarcely higher at 15. It’s a disappointing showing for two countries that have often been known for innovation in building science and practical application.

The good news is that the achievements needed to meet the benchmarks set by ACEEE are completely achievable. In ACEEE’s words: “The conditions required for a perfect score are currently achievable and in practice somewhere on the globe. For every metric, at least one country (and often several) received full points.”

Why This Matters

I think that everyone involved with the construction industry in both Europe and North America would benefit from better communication among the parallel channels of commerce, technology, and science. We rarely need to reinvent the wheel these days, and during those few points in history when we DO need to invent something, the process goes a lot faster if we have the help of knowledgeable collaborators everywhere.

I think that everyone involved with the construction industry in both Europe and North America would benefit from better communication among the parallel channels of commerce, technology, and science. We rarely need to reinvent the wheel these days, and during those few points in history when we DO need to invent something, the process goes a lot faster if we have the help of knowledgeable collaborators everywhere.

We can all benefit from the sharing of knowledge across the construction industries and among countries. Like sending our children away on a foreign exchange program, our ideas are often much richer when they return home. What do we gain from this type of exchange?

- We save money, in both industry and government, by avoiding duplicate research and development.

- We gain access to a bigger pool of human resources by working alongside professionals everywhere.

- We meet targets for energy efficiency, emission reductions, or other metrics more quickly when we share and implement the very best practices as they are developed in all markets.

- We solve problems within our own organizations by expanding our knowledge base to include others who are addressing the same issues.

International cooperation is not a new concept. But the difference, at this point in history, is that we now have the means and motivation to build new powerful collaborations among individuals and small organizations, giving us the potential to bypass the big slow-moving entities that have usually been our international emissaries. There are plenty of examples when this has happened in the past, and several areas where it’s about to happen in big ways in the housing industry. All we’re haggling over at this stage is who will have the foresight to support and benefit from these shifts.

Historical Examples

History tells us that we often develop technologies in North America and Europe on parallel but separate paths. In most cases, someone eventually looks at the work performed by their international colleagues and decides that it’s worth sharing, borrowing, or stealing. We have plenty of examples of this cross-pollination among separate-but-related technical camps. Witness these relevant examples.

Electrical Engineering

The early development of the electrical grid involved a melting pot of scientists and experimenters from around the world. One of the most influential of these may have been Nicolas Tesla (1856-1943), the Serbian electrical engineer who in the course of his storied career shopped his skills around Europe and then North America in search of collaborators and funders. He first gained the support of Thomas Edison and his ill-fated DC distribution scheme. He ultimately teamed with George Westinghouse, and when his alternating current system was established in North America, it was indelibly imprinted by Tesla’s work.

Rocket Science

When aerospace engineers in the United States began the process of creating a space program after the Second World War, they knew they had a knowledge gap. It was a poorly kept secret that German engineers had gone farther in their research on rocketry than any other country’s program. So the U.S. government set about identifying these best rocket scientists, bringing them to the United States, and embedding them in research institutions. Though these programs were shaded by the politics of cold war, these brilliant scientists nonetheless performed the core research and development that made it possible for humans to visit the moon only twenty years later.

Passive House

The simple idea of improving upon the minimum building codes — by installing high levels of insulation, addressing thermal bridging, managing ventilation, and installing micro-HVAC systems — was first put into practice by visionaries in the Canadian R2000 Program during the 1970s. German experimenters subsequently picked up the nascent North American concept, perfected it as if the their lives depended upon it, and promulgated the standard under the banner of Passivhaus. When the improved package was brought back to North America decades later, and adapted under the banner of Passive House Institute US, the housing industry on both continents gained huge amounts of knowledge from the collaboration.

Current Hotspots

The current housing industry is now ripe for widespread international collaboration. I think that individuals and organizations that learn how to identify and leverage specific market blind-spots will gain advantages over their stay-at-home competitors. Though it may seem daunting to embark upon the industry-shifting initiatives outlined here, there are immediate and simple opportunities embedded within each broad topic that can be implemented right away by any forward-looking individual.

Knowledge Exchange

It’s been almost a generation now since we started assembling web-based knowledge management systems in government, schools, and industry. Yet, much to the detriment of the housing industry, many well-meaning organizations still tend to shelter a lot of their knowledge within their proprietary silos. In some cases, these creators of knowledge have attempted to share their resources with others, but oftentimes the average user cannot wade through the flood of randomly dispersed information to find the knowledge they need.

Though there may have been a day when privatization of knowledge had its benefits, or when simply “posting it to the internet” meant that knowledge had been effectively shared, that time is clearly past. What we now need is organizations who can identify, organize, and share knowledge in ways that are transparent and widely accessible to users of all skill levels. We have already seen the huge value that’s added to organizations in other sectors when information is aggregated and shared across borders and throughout organizations. But no has come close to doing so in the housing industry.

“I think there is a huge opportunity waiting for organizations who learn how to super-charge the management of technical knowledge, translate it to the most common languages, and share it with researchers, managers, and on-the-ground practitioners everywhere.”

Portability of Credentials

The professionals who work in the housing industry will always need ongoing training to stay abreast of evolving methods, materials, tools, and standards. Their employers and collaborators will always look to credentialing organizations to qualify members of the workforce. Yet the market today is littered with an excess of conflicting and overlapping credentials, creating doubt for everyone about the value and practicality of credentialing. This also makes it difficult for individuals and organizations to work across borders.The high-performance construction industry needs a standardized set of international professional credentials that are general in scope and universal in application, so that every government, company, and individual can understand, support, and apply them.

The professionals who work in the housing industry will always need ongoing training to stay abreast of evolving methods, materials, tools, and standards. Their employers and collaborators will always look to credentialing organizations to qualify members of the workforce. Yet the market today is littered with an excess of conflicting and overlapping credentials, creating doubt for everyone about the value and practicality of credentialing. This also makes it difficult for individuals and organizations to work across borders.The high-performance construction industry needs a standardized set of international professional credentials that are general in scope and universal in application, so that every government, company, and individual can understand, support, and apply them.

“The housing industry will be one step closer to maturity when an organization, or a consortium of organizations, promulgates a set of professional credentials that are aligned with accepted best practices, and are recognized in both Europe and North America.”

Standardization of Best Practices

The design, construction, and maintenance of buildings is subject to the same rules of science and physics everywhere. Yet our attempts to describe those practices—our codes, standards, and regulations—are complicated, contradictory, and sometimes just plain wrong. It will never be a simple thing to harmonize building practices, since we’ll always need to account for regional variations in climate, soils, materials, fuels, and traditions. But the current hodgepodge of best practices creates barriers to innovation and improvement that have sometimes crippled the advancement of high-performance construction.

The housing industry is ready for a comprehensive set of prescriptive standards that are coupled with a realistic protocols for performance testing. We already have several examples of at-least-partial best practices in existence in North America and Europe. They give us a good place to start, though they’ll need to be expanded, aligned, and, ultimately, harmonized with the building codes.

“We now have the means to assemble a nimble and realistic collaboration — with individuals from every region — that gathers all of our best practices into a comprehensive and accessible system. It’ll happen when the most forward-looking individuals and organizations see what’s possible, gather the best minds from everywhere to do the work, and build a smart collaborative platform to capture the best knowledge.”

How to Build Your Own Professional Bridges

Each of these challenges will require the involvement of committed individuals who understand the power of modern collaborative tools. I offer here some ideas to help you expand your ability to work with others:

Include the rest of the world in your research

You’ll be surprised how much you learn if you expand the geographical reach of your inquiries. It’s easy if you’re working on the web. Whether you’re studying the effects of pollutants on human health in the U.S., searching for that perfect German detail for an air barrier, or looking for statistics on home energy consumption in France, you’ll benefit from the exposure to other methods, materials, and programs. You’d be surprised how many people around the planet face the same opportunities and issues that you do.

Develop new professional relationships

It’s become ridiculously easy to connect to colleagues all over the world. A good way to do so is through LinkedIn groups, Google Plus communities, or other social media. Start by identifying a group that addresses an area in which you’re interested, do some research into the topic, make a few posts, share some photos, and ask questions of international professionals who share your interests. Wherever you live, I can assure you that people will be thrilled that you’ve reached out to them. And if you are so lucky as to travel internationally, it’s a bonus to arrive in a country where you have professional connections.

Don’t worry about the language barrier

Don’t let your lack of a second language stop you from connecting with others. International communication has become easier than ever as English ascends to become the language of commerce. But if you are studying a second language, it’s a great idea to keep at it. Try, for example, scheduling a free web-based language exchange with an allied professional on a website such as Verbling, where you can engage in a no-obligation language practice with other learners. It’s a bonus if you connect with allied professions in a far-off place during these exchanges, and you’ll gain a greater grasp of your own skills when you need to explain them in a second language!

Where We Stand

We’re all part of the new globalization, whether we actively choose to participate or not. I view this flow of ideas, materials, and people as simply another stream of raw materials to be utilized to great advantage for everyone.

For each of us, it’ll take some time to learn how to work with these global resources, to sort the wheat from the chaff, and to integrate the new knowledge into our organizations.

But the opportunity is huge, and the future will include big options for those who learn how to reach out, connect with allied professionals in smart and responsive ways, and manage this new flood of knowledge.

— Chris Dorsi